Ngai Tai Origins

Ka tau ai te Kokoeā

Ka whaiwhai ake te Mātuku Moana

Ka kai te Kererū

Ka tiaki tūtei te Ruru

Ka korihi, ka tangi

Ka tangi, ka korihi

Ka korokī ko Ngāti Tai

Ko Ngāi Tai ka korokī

Tihei Mauri Ora.

Ko Kohukohunui ko Ngā Pona Toru ā Peretū ko Moehau ngā maunga

Ko Wairoa te awa

Ko Te Marae o Tai ko Te Waitematā ko Tīkapa ko Te Manukanuka ngā moana

Ko Tāmaki Makaurau te whenua

Ko Ngāti Whatatau ko Ngāti Wharetuoi ko Ngāti Rangi ko Ngāti Kōhua ko Ngāti Taurua ko Te Ngungukauri ko Ngāti Te Rau ko Te Uri o Te Ao-Tāwhirangi ko Te Patukirikiri ko Ngāti Tai Manawaiti ko Ngāti Tai Horokōwhatu ko Ngāi Tāiki ko Ngāti Taihaua ngā hapū.

Ko ngā marae maha.

Ko ngā whetū ki te rangi, ko ngā kirikiri ki te one taitapa, ko ngā mana whakaheke o Ngāi Tai.

Tēna

tātou katoa.

We of the sacred footprint in the earth

the footprints of the high-born

the footprints on our foreshores

Tapuwae o Nuku

Ngāi Tai have a long unbroken genealogy and occupation of their lands, waters and seas extending from the aboriginal inhabitants, pre-dating Kupe, Toi Te Huatahi and the great migration. Although our whakapapa best describes our hononga to the whenua, we have a tino taonga of Ngāi Tai which is a tohu (symbol) currently residing in the Auckland Museum - being a fossil human footprint dating from the founding eruption of Te Rangi-i-totongia-ai-te-Ihu-o-Tamatekapua (Rangitoto) over 600 years ago. This footprint was discovered on Te Motutapu-o-Taikehu, a place long held sacred to Ngāi Tai for their many wāhi tapu and association with Tupua of the motu (islands).

Tapuwae Ariki

Smaller footprints remind us of the many descendants and mokopuna, who have crossed this region over that long period of time. Larger footprints remind us of our high-born chiefly lines (Ariki) and ancestors. These remind us of how important those leaders were and their value as navigators through our history.

Tapuwae o Tai

Our tribal name Ngāi Tai, resounds as the story of a maritime people unencumbered by any normal sense of boundaries. Where our vision was only limited by our imagination, it was the same vision, honed by thousands of years of exploration, facing the challenge of navigating the world’s greatest ocean for survival. These descendants of Māui today carry his DNA and values into the new world of Ngāi Tai, true inheritors and worthy recipients of a boundless legacy left by the ancients and their numerous descendants.

“Ko ngā whetū ki te rangi, ko ngā kirikiri ki te one taitapa, ko ngā mana whakaheke o Ngāi Tai.”

“As the stars in the sky and the grains of sand on our many foreshores, so are the myriad chiefs in the Pantheon of Ngāi Tai forebears.”

‘Te Tōtaratahi’ at Te Onewa Pā

Ngāi Tai

Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki are acknowledged as being amongst the original inhabitants of Aotearoa. This document summarise our histories, from our connections to the Tipua, Turehu and Patupaiarehe, to our whakapapa links with the earliest settlers of these lands. It is inevitable that some of the most significant sites of arrival, ritual, landmark and subsequent habitation, both seasonal and permanent, are now shared with others, others with whom we share close links through whakapapa and shared histories, others who through the passage of time and history hold ahi kaa in different places. Ngāi Tai hold fast to the knowledge of our associations to the places and the people as taonga tuku iho. From Te Ārai out to Hauturu out to Aotea and throughout Hauraki and Tāmaki Makaurau and all the islands within, Ngāi Tai have significant multiple, and many layered associations.

Herein also lies the kōrero of how the Ngāti Tai of Tāmaki were united with Ngāi Tai of Tōrere to form the modern entity that is Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki today. Through this union, as well as many others that reinforced Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki connection to the wider hapū and iwi of Tāmaki, Ngāi Tai have maintained an ancient ancestral foundation of ahikāroa to the Tāmaki rohe and its maunga, motu, moana, its well utilised waka portages and waterways.

It is by this history which predates the great fleet era that Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki are intimately attached to founding kōrero of the wider rohe from Te Hūnua across to Waitākere, from the North Shore Te Whenua Roa a Kahu, and out to Te Manukanuka a Hoturoa, Manukau Harbour.

Tipua, Tūrehu and Patupaiarehe

Our earliest oral histories of the Tāmaki region refer to the Tipua, Tūrehu and Patupaiarehe - divine ancestors from Rarohenga that were capable of traversing the upper and lower realms of existence, and credited with raising volcanoes and similar cataclysms.

Matakamokamo and Matakerepo

A key narrative to these histories attributes the formation of some of our prominent landmarks to the Tipua husband and wife known as Matakamokamo and Matakerepo. Together these Tipua, along with the deitys Mataaho (deity of volcanic activity) and Mahuika (ancestress of fire), were responsible for the creation of Lake Pupuke and the emergence of Rangitoto causing the formation of the tuff craters ‘Ngā Kōpua Rua,’ ‘Te Kopua a Matakamakamo’ at Awataha, and ‘Te Kopua a Matakerepo’.

Matakamokamo instructed Matakerepo to weave him some new garments but was dissatisfied with the finished product and argued bitterly with his wife. As the couple argued, their house fire went out and could not be rekindled causing Matakamokamo to curse Mahuika, the goddess of fire. Mahuika then called on Mataaho to ignite a volcanic eruption to punish the couple.

The couple lived atop Te Rua Maunga, situated in present day Pupuke Moana. Mataaho caused Te Rua Maunga to sink beneath the earth leaving Pupuke Moana in its place. Mataaho also rose Rangitoto from the sea, where Matakamokamo and Matakerepo fled in panic.

Matakamokamo and Matakerepo later returned to the mainland only to be welcomed again by the wrath of Mataaho.

The couple were turned to stone and sank beneath the ground along the western foreshore of Oneoneroa thus forming Onepoto and the tidal basins of Matakerepo and Matakamokamo

Te Pakuranga-Rahihi

Another korero of significance to Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki is the ancient Tūrehu legend of Te Pakuranga-Rāhihi (The Battle of the Sun’s Rays), the narrative of which envelopes the Ngāi Tai core territories of Te Hūnua, Ōhinerangi (Maraetai beach), Ōhuiarangi (Pigeon Mountain), and Pakuranga.

The legend begins with the daughter of Koiwiriki, a Tūrehu chief of Hūnua-Papakura. Koiwiriki’s daughter, Hinemairangi, is said to have eloped with a young Turehu chieftain of Waitakere known as Tamareia, the son of Pūtere, chief of the Nukumaitore hapū of Waitakere. Koiwiriki, in anger of his daughters eloping, raised a war party against Nukumaitore of Waitakere to forcibly retrieve his daughter.

What followed was the great battle known as Te Pakuranga Rāhihi which began at Ōhuiarangi. As the battle progressed, neither side were able to gain advantage until the tohunga of Koiwiriki caused the sun to rise prematurely. This caught the people of Waitakere by surprise, and many of them perished in the sun’s rays (It is said that the Turehu or patupaiarehe came out only at night and withdrew to the forests at sunrise).

Koiwiriki then continued his war party on to Waitakere. The Tohunga of Nukumaitore saw the war party advancing and, in response, caused volcanoes to erupt around them, enveloping them in the ash and, finally, burying them in the molten lava flows. These eruptions caused the retreat of the remaining Hūnua peoples back into the depths of the ranges.

It is said that Hinemairangi was herself caught in the path of and affected by the sun’s rays during the battle at Ohuiarangi, and was thus transformed to stone. Hinemairangi still stands today at the foreshore of Maraetai beach at the spot known as Ōhinerangi, regarded as a Mauri for Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki and a (Toka tū ki te takutai) Kaitiaki of the Maraetai district.

Sunset at Raupoiti, Motutapu

Te Tini o Maruiwi, Te Tini o Toi

Ngāi Tai understand that the very first Polynesian settlers landed in three waka on the Taranaki Coast at Ngamotu. These canoes were Kahutara, Taikoria and Okoki, commanded respectively by Maruiwi, Ruatāmore, and Taitawaro. These family groups increased in numbers and became known as Te Tini o Maruiwi, Te Tini o Ruatāmore, and Te Tini o Taitawaro.

The son of Maruiwi, Tāmaki, went on to lead the people of Te Tini o Maruiwi to settle the land now bearing his name. Tāmaki’s daughter was the ancient pre-Tainui ancestress Huiarangi of Te Tini o Maruiwi and Ngāti Ruatāmore, from whom Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki trace descent by the marriage of the founding Ngāti Tai ancestors Hinematapāua of Ngāti Ruatāmore and Tiki-te-auwhatu (Te Kete-ana-taua) of Tainui waka; parents of the eponymous ancestor Taihaua.

When the great ancestor Toi Te Huatahi arrived in Tāmaki he found it to be extensively settled already by the Maruiwi peoples as firstly evident by the many occupation fires visible from his arrival. Hence, Toi called this land Hawaiiki tahutahu, ‘Hawaiiki of Many Fires’.

In Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki traditions, two key Maruiwi ancestors emerge as prominent in the time of Toi’s arrival, namely Huiarangi (the daughter of Tāmaki, noted earlier), and Peretū.

Peretū (pere, dart; tū, pierced) was so named for his father died of a wound in battle caused by a hand-thrown dart, a weapon that was commonly used by these ancient peoples. The headland where Peretū resided is named Ō-Peretū (Fort Takapuna). Peretū had other Pā across Tāmaki, one such in the North being Te Raho-Para-a-Peretū at present day Castor Bay, North Shore, and another in the south known as Te Pounui a Peretū (Ponui Island).

At that time Peretū utilised Rangitoto for the purpose of a “Rāhui-Kākā” (Parrot Preserve), a bird then very abundant on that island. The many Kākā would thrive on the plentiful bush foods of Rangitoto for the island was covered in a forest of Rātā and Pohutukawa trees. For this reason the slopes of Rangitoto are known as “Ngā Huruhuru a Peretū” (The hairs of Peretū) in ancient times and today. Note that this period precedes the second eruption of Rangitoto.

Some of Toi’s crew stayed and intermarried with Peretū’s people. Uika, Toi’s cousin, was one who stayed in Tāmaki and intermarried. Uika settled at present day North Head, known thereafter as Maunga-a-Uika or Maungauika.

Also in these ancient times was the name Ngā Pona Toru a Peretū (The three knuckles of Peretū) which refers to the three summits of Rangitoto. Peretū had three fingers on each hand; this was not a deformity, but a sign of his descent from a godly ancestor.

Ma te tuhi rapa a Manawatere ka kitea

By the vivid mark of Manawatere it will be found

This Ngāi Tai Pēpeha refers to seeking for the correct path by the ways and direction shown by Ngāi Tai tūpuna.

It is said that early ancestor of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Manawatere, arrived on his waka Huruhurumanu (Birds feather) so called for it is said his waka glided over the ripples of the waves like a feather.

Manawatere landed Huruhurumanu at present day Cockle Bay and named the bay Tūwakamana.

He then proceeded to leave his (tuhi) mark on a Pohutukawa tree (Te Tuhi a Manawatere) with an ochre (karamea) from the area, by which his relatives would find him. The mark of Manawatere was intended to show that he had been there and that they should settle in that area. This tohu is said to resemble a ‘double S, on its side’. Manawatere then settled in the Maraetai area and built a pā /kaīnga named Ōmanawatere (The place of Manawatere).

Manawatere later ventured on a fishing expedition to Ōrāwaho passage between Rangitoto and Motutapu arriving at Ōmokonui o Kahu (Islington Bay, Rangitoto). It was here that Manawatere drowned. This was due to Manawatere not being conversant with the karakia necessary to placate the resident kaitiaki ngārara of Rangitoto and Motutapu.

His body was washed up on the shore at the area of Home Bay, Motutapu, after which was known as Te Pēhi a Manawatere – The Submerging of Manawatere.

These aforementioned ngārara (reptiles) are named Moko-nui-o-Kahu (Great Lizard of Kahu) and Moko-nui-o-Hei (Great Lizard of Hei). Kahu-matamomoe left one at Pēhi-manawa (Home Bay, Motutapu), and the other at the Rangitoto foreshore, near Orawaho. One belonged to Kahu, the other to Hei, his uncle. They are still to be seen at these places at Rangitoto and Motutapu, now turned to stone.

Waka Tainui

Before entering Te Waitematā, Tainui and its crewmembers carried out tapatapa and uruuruwhenua rites for entering new lands and waters at Tikapa Moana. Of importance to modern day Ngāi Tai the Tainui traditional kōrero speaks of the waka anchoring within the stretch of Te Whakakaiwhara coastline known as Tararahi, ‘many Terns’. Here they saw the wide river mouth of a long river naming it Te Wairoa after the familiar Te Vairoa in Tahiti.

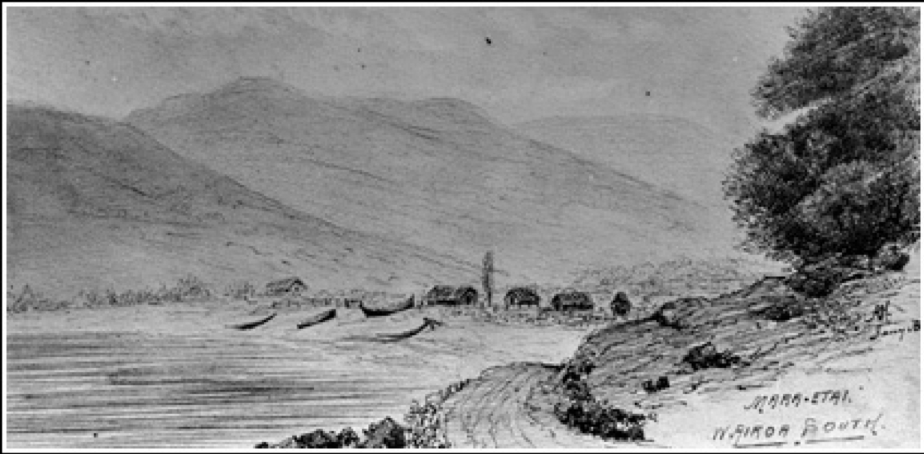

The people of the waka went ashore and made a feast of the ‘Whara’ flowers from the kiekie vine hence it was known thereafter as Te Whakakaiwhara (The feastmaking of Whara). Here one of the crew, Tāne Whakatia, planted a Karaka seed within a rock crack which grew to provide a sacred grove called Te Huna a Tāne, this grove continues to flourish to this day. Once the ceremonies were complete at Te Whakakaiwhara, the waka moved into the long tidal passage which they named Te Maraetai ‘The Marae of the Tides or ‘Enclosed Tide’, this area being directly in front of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki’s present day Marae, Umupuia.This name was given as the sea was so calm as to resemble an ‘Atea’, courtyard enclosure of a Marae.

The Tainui carried on to Waipaparoa (expansive waterfront) at Tūwakamana (Cockle Bay)and past Kahawairahi (abundant kahawai) at Beachlands, Pine Harbour.

Ngāti Tai tradition states that the Tainui entered the mouth of the Tūranga Estuary where it tethered up to a large volcanic rock in the shape of a man (Tūranga) meaning ‘anchorage’ or ‘standing place’. The name Tūranga also refers to the rivers western bank hill and the immediate surrounding local settlements established by Ngāti Tai. It is said the waka anchored at Motukōrea (Brown’s Island), opposite Te Naupata, prior to travelling to Rangitoto and Motutapu where Taikehu, a tohunga of the Tainui waka and the brother of Hoturoa’s (Captain of Tainui Waka) wife, Whakaotirangi, ascended the summits of Ngā Pona Toru a Peretū (Rangitoto) and gave his own name to its peaks being Ngā Tuaitara a Taikehu (The dorsal fins of Taikehu). He named the neighbouring island Te Motutapu a Taikehu thus claiming a new home for his descendants.

Ngā pōtiki toa ā Taikehu

Ngā tamariki toa a Taikehu

The brave, young children of Taikehu

An account of Taikehu and Tainui waka in the Manukau recalls an abundance of mataitai (seafood) and seabirds; Taikehu and his companions waded through the Manukau, the harbour flourishing with jumping kanae (mullet), so much so that Taikehu and his companions were able to catch one in each hand. So as to take possession of the fishery, Taikehu named the fish “Ngā tamariki toa o Taikehu”.

A similar proverb applies to Taikehu’s Ngāti Tai being so numerous on the waters of the Waitematā that they are likened to a multitude of kataha (herrings):

Ngā waka o Taikehu me he kāhui kataha kapi tai

The canoes of Taikehu like unto a shoal of herrings filling the sea

Taikehu continued aboard Tainui, sailing close in to Te Haukapua (Torpedo Bay), beneath the headland of Te Kūrae a Tura (Duder’s Hill). Tainui then became stranded on a sandbank immediately offshore. Taikehu’s efforts to remedy the situation by swimming ashore have been recognised by names for the significant challenges he encountered in his efforts. The sandbank upon which Tainui was stranded was named Te Ranga o Taikehu, with the adjoining stretch of water named Te Kaunga o Taikehu (The Swimming of Taikehu), and the place he came ashore was named Te Tāhuna o Taikehu (The Sand Dune of Taikehu).

The present day reclaimed land that Ports of Auckland sits on is known as Wai-a-Taikehu.

Taikehu and his people were received and hauled ashore by the tangata whenua residing at nearby Maunga-a-Uika, descendants of those of Te Tini o Toi whom had intermarried with Peretū and Uika. There the Tainui crew drank from a spring on the slopes of Maunga-a-Uika, which they named Takapuna (The Knoll of the Spring). From Te Haukapua, Tainui returned to Ōmokonui-a-Kāhu at Ōrawaho (Islington Bay) and found the Arawa waka moored. A quarrel arose between Tamatekapua (Arawa captain) and Hoturoa and the two rangatira came to blows and during the contest Tamatekapua was struck on the nose which bled, after which the island was termed (Te Rangi-i-totongia-ai-te-ihu-a-Tamatekapua). As they were close relatives their people intervened and ceased the duel.

From Ōrawaho, Tainui continued to the mouth of the Tāmaki estuary, thereafter named Te Wai o Tāiki (The waters of Tāiki) also known alternatively as Ōtāiki. Tāiki being one of eleven ancestors who are recorded to have disembarked the Tainui to stay and settle into Tāmaki.

Tāiki was also associated with settling in the Awataha area of the North shore of Te Waitematā where the name Ngā Huru ā Tāiki was given to a sacred Pūriri in which tapu items were concealed by his descendants.

The Tainui continued and moored up at Waiorohe below Taurere (Taylor’s Hill, Glendowie). As aforementioned, at Taurere the rangatira Tiki Te Auwhatu (also known as Te Kateanataua) settled and married a local woman named Hinematapāua, a descendant of the already established Te Tini o Toi.

From Tiki Te Auwhatu (Te Keteanataua) and Hinematapāua came forth Taihaua, acknowleged as a founding ancestor of Ngāti Taihaua an important hapū and descent line for present day Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki

The rangatira Horoiwi was another who left the waka at Waiorohe and proceeded to marry Whakamuhu, a cheifteness of the locality.

Horoiwi proceeded to set his Paa next to his wife’s (Whakamuhu Pā) and it was named thereafter as Te Pane o Horoiwi (Achilles Point, St Heliers).

According to Ngāi Tai traditions involving the Tainui waka, the upper area of the Tāmaki Estuary beyond Te Wai o Tāiki was given the name Te Wai Mokoia (The Waters of Mokoia). This was derived from the shortened name of a kaitiaki Taniwha called Moko-ika-hiku-waru (Great reptilian sea creature of the eight tails). Mokoikahikuwaru, one of the Tainui waka taniwha, remained and took up residence at the entrance to the lagoon Wai-roto-o-Mokoika (Panmure Basin). This Taniwha also dwelled within the lagoon to drink of the spring waters of Te Waipuna o Rangiatea so named by Taikehu in memory of their old home in Rangiātea (Ra’iatea).

After exploring these places Taikehu and his party rejoined the Tainui to inform their crewmembers of the findings around Tāmaki.

Taikehu stayed on and settled in the lands of Tāmaki Makaurau between the waters of the Manukau, Waitematā Tikapa Moana and Motutapu. Motutapu in particular was the base of Taikehu and his Ngāti Tai followers

Te Hekenga Tokotoru

The Migration of the Trio

During earlier travels of the Tainui, the daughter of the Captain Hoturoa; Torere, went on to marry the chief Manakiao of the area in which they would settle, the area that was to take her name. It is through this connection that Ngāi Tai ki Tōrere and the Ngāti Tai ki Tāmaki trace the origin of their kinship.

Some twelve generations ago, competition for good cultivation land at Torere had led to bitter and lengthy warfare amongst the local people. The elderly chief, Tamatea Tokinui, as he prepared himself for death, delivered his ōhākī to his people, telling them:

O children go! depart [sic] hence to your relatives there at Hauraki. For here is incessant family strife and death—turmoil unending with your relatives here. Go and seek peace in that our other home. For here in this one, home is death—there in that second home life is assured.

Ka mate kāinga tahi, ka ora te kāinga rua

When one home fails, have another to go to

So his children agreed, and when Tama had departed his life, his three (grand)daughters prepared to lead the family (hapū) to Hauraki. Hence the name of the heke, Te Heke-o-Nga-Toko-Toru (The Migration of the Three).

And so the three chiefly sisters, Te Raukohekohe (the eldest), Te Mōtū ki Tāwhiti, and the youngest sister Te Kaweinga led between 100 and 500 peoples from Tōrere up the coast via Tauranga to the rohe of Ngāti Maru. It is here at Papa Aroha (north of present day Coromandel) that they were joined by a party of guests from Waitematā and Maraetai, the relatives that Tamatea Tokinui had spoken of. This group belonged to Ngāti Tai, Te Wai o Hua and specifically the hapū of Te Uri o Te Ao, and were led by their rangatira, Te Whatatau.

Te Whatatau had brought his wife, Te Kaweau, to her Ngāti Maru people to observe the ceremonial rituals required for the arrival of her first child, however, during this visit, Te Whatatau was embarrassed by Te Kaweau’s jealous refusal to share potted birds with the three sisters. Subsequently Te Whatatau abandoned Te Kaweau to remain with her people, taking Te Raukohekohe and Te Mōtū ki Tāwhiti as wives with the youngest sister, Te Kaweinga, remaining at Hauraki where she married Te Whiringa, a rangatira of Te Uri o Pou/Te Wai o Hua and Ngāti Tai descent.

Me mahara ki te hē o Kaweau

Remember the error of Kaweau

Te Whatatau and Te Raukohekohe went on to have two sons, Rongomaiaahua and Te Wana.

Te Uri o Te Ao hapū (named after Te Whatatau’s father, Tāmaki Te Ao) controlled the lands extending between Te Waitematā and the Wairoa River, including the lands of Maraetai and Umupuia. Te Umupuia, was then known as Te Kuti, or Te Ku-iti, so named after a narrow little stream running from Pukekawa (the highest peak behind Umupuia Marae) down to Umupuia Beach.

Following the marriage of Te Raukohekohe and Te Whatatau, the land of Te Kuti was gifted to Te Raukohekohe and her people as “a place to hang their nets” (i.e. a seafood gathering resource), and the Ngāi Tai, Ngāti Tai and Te Wai o Hua people of the Maraetai and Wairoa (Clevedon) districts began to regularly congregate on the land. Te Raukohekohe’s followers were also gifted lands at Pōhaturoa (Maraetai Beach), Te Wai o Maru (Waiomanu Reserve) and lands further inland up the Wairoa River. When unified under Te Wana they became the Ngāti Te Raukohekohe, or Ngāti Te Rau hapū of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki.

In adulthood, Te Wana claimed the lands at Te Wairoa and Maraetai by promising to unite all of the hapū of the area as one iwi - Ngāti Tai.

Those united by Te Wana include the Ngāi Tai migrants from Tōrere, the Te Uri o Te Ao of Ngā Iwi/Te Wai o Hua, the Ngāti Tai and the Ngāti Manawaiiti people of Tāmaki and the North Shore, plus the many hapū of Te Wairoa and Te Maraetai. The full name of Te Wana became Te Wana Hui-kāinga Hui-tangata (Te Wana, the Gatherer of Villages, the Gatherer of People). As a great warrior he was sometimes referred to as Te Wana Hui-kauae Kai-tangata.

In Ngāi Tai tradition Whakakaiwhara Pa and nearby Te Oue Pa are identified as being the main homes of the leading rangatira, and as being the focal points of the Ngāi Tai occupation of the wider district. They served as major defensive sites for our tribe.

This chapter introduces the associated hapū of Ngāti Tai/ Ngāi Tai and the subsequent bonds of intermarriage to the wider iwi and hapū of the rohe. See Treaty Claims documentation and whakapapa for more detailed information for each.

According to Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki whakapapa and land court records, the Maraetai coast from Tāmaki to south of Ōrere was occupied by closely related hāpu of Ngāi Tai, Te uri o Pou and Te Wai o hua, who were living together as ‘one people’.

Ngā Hapū o Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki

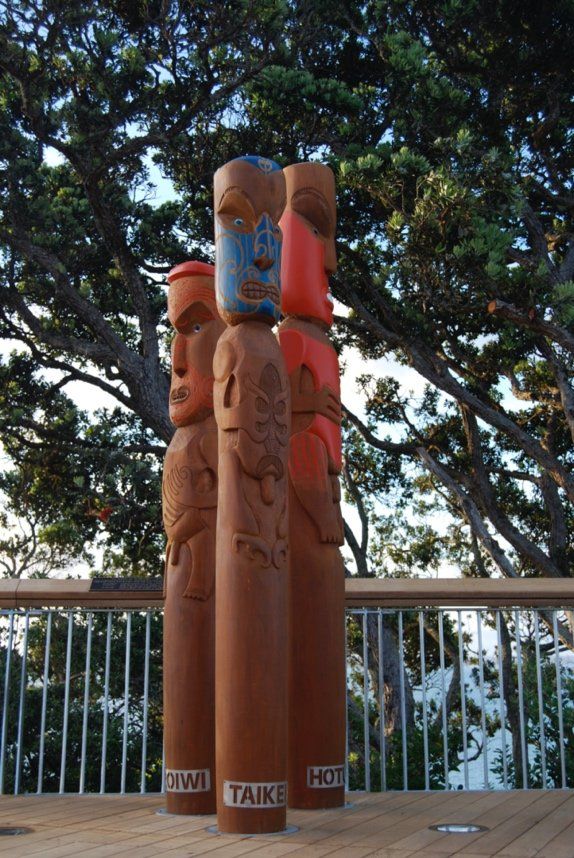

A shared Ngāi Tai and Ngāti Paoa carving at Tāwhitokino.

Rongo-mā-Tāne. A Ngāi Tai carved Rakau Atua at Te Auaunga.

Potaka of Te Uri o Te Ao at Te Maungarei o Potaka

Te Haerenga

The peoples of Ngāi Tai and associated hapū enjoyed a period of relative peace, prosperity, and trade across the wider rohe. This period of ‘Whenua Rangatira’ came to an abrupt end following the influences that resulted from Pakeha contact and subsequently the arrival of the musket.

During several musket-armed Ngāpuhi raids of neighbouring Ngāti Pāoa and related groups in the 1820’s, the Hauraki tribes were devastated and the area de-populated. Ngāi Tai at Maraetai and Te Wairoa areas initially avoided attack due to the fact that Kapotai after whom the Ngāpuhi group ‘Te Kapotai’ were named, was the grand nephew of Huarere from whom Waiohua and Ngāi Tai took descent.

This link however did not protect Ngāi Tai indefinitely from Ngāpuhi attack. Te Tirarau's war party eventually arrived, having heard that Tara Te Irirangi's daughter Te Whakakohu was a fine woman. Te Tirarau had struck Ngāi Tai at a vulnerable time as Te Irirangi had gone to purchase arms at Whakatiwai. Ngāpuhi took captive Te Whakakohu, Ngeungeu Te Irirangi and others from the Totara pa on the Western side of the Wairoa River. Ngāi Tai was devastated having been armed only with traditional weapons.

Some of those who survived this attack took refuge with their Tainui relatives in Waikato and were to remain there until the mid 1830's. A small number of the tribe did however remain behind, and so the ahikāroa of Ngāi Tai was never extinguished.

During these early times, the Ngāi Tai chiefs who dealt with Pakeha were people like Tara Te Irirangi, Nuku (who also took on the Pakeha name of Anaru, and after whom, Tara Te Irirangi's grandson was named), Wi Te Haua, Hori Te Whetuki, Watene Te Makuru and Honatana Te Irirangi. All these people were all born towards the later part of the 18th century.

With the passing of Nuku, the mantle of rangatira passed to Tara Te Irirangi. Both were great grandchildren of Te Wana. Tara Te Irirangi had great mana within Ngāi Tai and also surrounding tribes such as Ngāti Paoa, As mentioned earlier he was able to use his influence to provide patronage and support for his Pakeha son in law Thomas Maxwell.

After the death of Te Irirangi, the mantle then passed to Hori Te Whetuki. Hori along with his cousins Honatana Te Irirangi and Watene Te Makuru continued to represent Ngāi Tai until they died. Men like Honatana Te Irirangi and Hori Te Whetuki lived in turbulent and difficult times. They lived through the turbulent times surrounding the land wars and the pressures on them would have been immense.

With the deaths of Hori Te Whetuki, Honatana Te Irirangi and others towards the end of the 19th Century, Ngāi Tai representation and leadership fell to Anaru Maxwell, Te Roto Te Whetuki, Te Paea, Henare Kingi, and the younger generation in Emere Beamish (Anaru's daughter), Hauwhenua Kirkwood, Paretutanganui Mita and Te Arani Brady, these last three being grandchildren of Hori Te Whetuki.

At Princess Te Puea Herangi’s establishment of the Tainui Māori Trust Board, Hauwhenua Kirkwood represented Ngāi Tai and Ngāi Tai land interests. When Hauwhenua retired, Ngeungeu Zister filled his vacancy and went on to serve on the board for 27 years. Wi Matau Taka of Te Koheriki then replaced her, holding the position until 1989, with Carmen Te Hinu Rangimoewaka Kirkwood then representing Ngāi Tai on the Board until it was dissolved in 1999.

The dedication of these rangatira and the Iwi eventually resulted in the settlement of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki’s historical claims, as agreed in the Deed of Settlement between Ngāi Tai (Tribal Trust) and The Crown, so beginning a new era for the people of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki.